This article was written by Ian Baird whose family loved Scarborough and he evenutally moved to the borough in the 1970s.

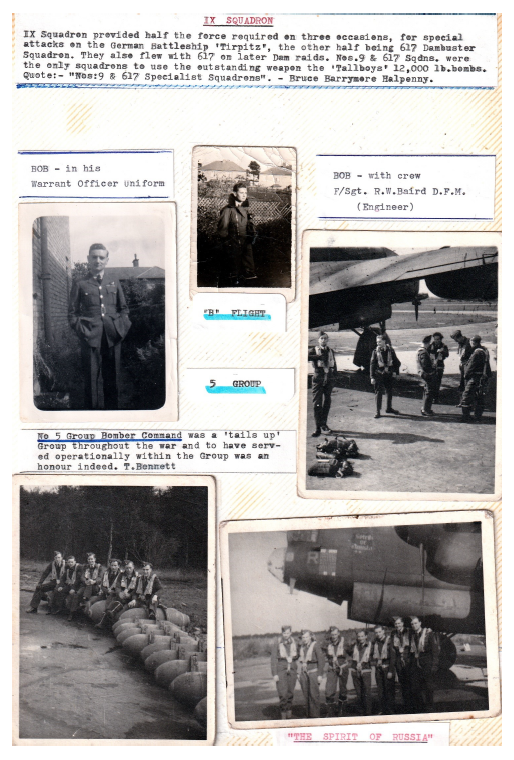

On 12th November 1944, my father, Flt Sgt Robert Baird was safely relaxing back at base after one of the longest sorties ever flown by Bomber Command during WWII.

At 20, he was the youngest member of any bomber crew on that momentous raid and as flight engineer, it was up to him to manage the fuel economy of the engines to ensure the crew's safe return. He'd done a similar thing a few weeks before, managing to bring the 7 crew, and the expensive, unused Tallboy bomb, all the way back from Tromsø in Norway.

But for this raid, new, more powerful engines had been fitted; so had extra fuel tanks. Regular equipment, protective armament and armour had been stripped away, and a crew member would be left behind, his mid-upper gun turret having been removed completely. The distance flown on this raid was to be 2,250 miles; time of take off from Lossiemouth and Milltown was between 03:00 - 03:30 and the time he'd land in back Fraserburgh was around 16:00.

For 12 hours and 30 minutes, 30 crews would be subjected to the incessant drone of the engines; be forced against every fibre of their bodies to use the hated Elsan toilet situated behind the bomb-bay; eat sandwiches and drink tea from flasks; fly low (1,000ft) over the sea to avoid radar detection; transgress into neutral Sweden to approach the target and gain surprise, and despite their fears, face but survive the most appalling mauling from the ship's own and augmented defensive armament, including its 15” guns, multiple shore mounted AA batteries, 2 flak ships and a squadron of very capable Focke-Wulf 190 fighters stationed at Bardufoss, just a few minutes flying time from the target.

And for what? To sink the German battleship Tirpitz; sister-ship to the devastating Bismark. And sink her they did and in the process, killed anywhere from 950 to 1,204 German sailors.

They also have left a controversy which has raged ever since as to which squadron actually sank the Tirpitz and how many hits were scored. I hope to tell the story as I truly believe it to be, as told to me by my father, who was there; from a Norwegian report on the raid compiled from eyewitnesses; from an account I heard, in person, from an eyewitness in Tromsø and confirmed by the then head of the Tirpitz Museum, Commander Leif Arneberg Royal Norwegian Navy. Finally, from the various accounts my mother collected when she tried to find out the answer to the question all little boys have asked their silent fathers, “What did you do in the war, Daddy?”

I have diagrams, maps and photographs to show you; magnificent artwork, and something more incredible, artefacts from the ship itself.

But first gentlemen, let me tell you about the Tirpitz, and why she was she became known as 'the Beast' to Winston Churchill. Why was she the subject of 28 separate, actual and planned attacks, by the RAF, the Fleet Air Arm, Russian bombers and Royal Navy midget subs; and by K-21 a Russian submarine, before being finally finished off, by the the two most specialised bomber squadrons in the RAF, 617 and IX, on their 3rd attempt, using the most powerful bomb then devised by Barnes Wallis, the 12,030lb, Tallboy?

Tirpitz was, by a narrow margin, the largest ship ever built for the Kriegsmarine. She was laid down in the Kriegsmarinewerft Wilhelmshaven in November 1936 and her hull was launched in 1939. Work was completed in February 1941 and she was commissioned into the German fleet. Tirpitz not only had virtually impenetrable armour (the deck was 5.9” thick and the sides, 12.6”), she also had a main battery of 8, 38cm (15”) guns in 4 twin turrets; 6 turrets containing twin, 15cm (5.9”) guns; 8 mounts of twin, 105mm (4.1”) guns; 8 twin 37mm (1.5”) cannon mounts and 12, single, 20mm (0.79”) FlaK 30 cannons. Later modifications added 46 extra 20mm FlaK cannons, 2 quadruple, 53.3cm (21”) torpedo tubes and improved radars – particularly to the 105mm AA guns. These and other changes made her 2,000 tonnes heavier than Bismarck, and the heaviest battleship ever built by a European navy.

Tirpitz displaced 42,200 tons as built - 51,800 tons fully loaded. She was 824' 6” long, had a beam of 118' 1” and a maximum draft of 34' 9”. Her standard crew of 103 officers and 1,962 men was increased to 108 officers and 2,500 men. She was powered by 3, Brown, Boveri & Cie geared steam turbines developing a total of 160,793 shaft-hp, giving her a maximum speed of 30.8 knots (35.4 mph) and a range of 10,350 miles.

Attempts to destroy her began during her construction as British bombers repeatedly attacked the harbour in which the ship was being built. On the 8/9th October 1940, 17 Hampdens attacked her in the the dry dock. On 8/9th January 1941, a total of 32 Wellingtons, Whitleys and Hampdens tried. On 29/30th January, 25 Wellingtons and 9 Hampdens attacked and on 28th/ Feb-1st March a total of 116 Blenheims, Hampdens, Wellingtons and Whitleys struck. Although no damage was caused to the ship, the attacks slowed the building work, and at the cost of only 1 Blenheim.

After sea trials, Tirpitz was stationed in Kiel for training in the Baltic. When Germany invaded Russia, a temporary Baltic Fleet was created to prevent the breakout of the Soviet fleet based in Leningrad. Tirpitz was briefly the flagship of the squadron, consisting of the heavy cruiser Admiral Scheer, the light cruisers Köln, Nürnberg, Leipzig, and Emden, several destroyers, and two flotillas of mine-sweepers. The Baltic Fleet, patrolled off the Aaland Islands until 26th September 1941, after which it was disbanded and Tirpitz resumed training.

The RAF continued to launch unsuccessful bombing raids on Tirpitz while she was stationed in Kiel. 28/29thMay only 3 of the 14 Whitleys sent reached the target area due to bad weather. On 20/21st June, 47 Wellingtons, 24 Hampdens, 20 Whitleys, 13 Stirlings and 11 Halifaxes failed even to find her: 1 Whitley and 2 Halifaxes were lost.

Tirpitz was then sent to Norway to prevent an allied invasion and to threaten the Russia-bound convoys. On 16th January 1942, British aerial reconnaissance located the ship in Trondheim. Tirpitz then moved to the Fættenfjord, just to the north, escorted by destroyers but the Norwegian resistance sent her location to London. The ship's crew even cut down trees and placed them aboard to camouflage her. They also frequently hid the entire ship inside a cloud of artificial fog, created using water and chlorosulfuric acid. Additional AA batteries were installed around the fjord, as were anti-torpedo nets, and heavy booms were placed in the anchorage's entrance. Fuel shortages kept Tirpitz and her escorts idle and ineffectual behind their protective netting.

Poor weather over the target meant an attack at the end of January, by 4-engined heavy bombers, couldn't find the ship. In early February, Tirpitz took part in the deceptions designed to distract the British in the run-up to Operation Cerberus, the Channel dash of the Gneisenau and Scharnhorst.

In March1942, Tirpitz, Admiral Scheer, several destroyers and 2 torpedo boats, were tasked to attack the homebound convoy QP8 and the outbound Convoy PQ12. Enigma intercepts warned of the attack, so the convoys were rerouted.

An air attack was launched by the Fleet Air Arm early on the 9th March; 12 Fairey Albacore torpedo bombers attacked the ship in 3 groups. 3 crewmen were wounded but Tirpitz successfully evaded the torpedoes, shot down 2 aircraft and returned to Trondheim. On 30th March, 33 Halifax bombers attacked the ship; they scored no hits, and 5 aircraft were lost.

The RAF launched a pair of unsuccessful strikes in late April. On the night of 27/28th April, 31 Halifaxes and 12 Lancasters attacked: 5 bombers were lost. The following night, another raid composed of 23 Halifaxes and 11 Lancasters, took place: 2 bombers were shot down.

The actions of Tirpitz and her escorts in March had used 8,100 tons of oil, which took the Germans 3 months to replenish. Convoy PQ 17, which left Iceland on 27th June bound for Russia, was the next target. However, shortly after Tirpitz left Norway, the Soviet submarine K-21 fired two or four torpedoes at the ship. Although the Russians claimed two hits, all the torpedoes missed. Meanwhile, Swedish intelligence had reported her departure to the British who ordered the convoy to disperse: result, 21 of the 34 transports were sunk.

Tirpitz returned to Altafjord, then moved to Bogenfjord near Narvik for a major overhaul. Hitler forbade the ship to return to Germany, so this was done in Trondheim. The defences of the anchorage were strengthened: the additional anti-aircraft guns were installed aboard, and double anti-torpedo nets were laid around the vessel. The repairs were done in phases so that she would remain partially operational.

During the overhaul, an attack was tried using two Chariot, human torpedoes. However, before they could be launched, rough seas caused them to break away from the fishing vessel which was towing them.

Scharnhorst arrived in Norway in March 1943, but Allied convoys to Russia had ceased temporarily, so Admiral Dönitz ordered an attack on Spitzbergen. During the bombardment, Tirpitz fired 52 main-battery shells and 82 rounds from her 15cm secondaries. This was the first and only time the ship fired her main battery at a surface target. An assault force destroyed the shore installations and captured 74 prisoners.

As all the bombing attacks had been ineffectual, the British decided to use the newly designed X craft midget submarine. Thus Operation Source: the X craft were towed to their start point; they'd penetrate the anti-torpedo nets and each drop 2 powerful, 2-tonne mines under the target. 10 X craft were sent on the operation but only 8 of them reached Kåfjord. The raid began early on 22nd September 1943. X5, 6, and 7, successfully breached Tirpitz's defences; X6 and X7 managed to lay their mines. X5 was detected 200m from the nets and sunk.

The mines caused extensive damage; the first exploded abreast of turret Caesar, and the second detonated 50 yards off the port bow. A fuel tank ruptured, shell plating was torn, a large indentation was formed in the bottom of the ship, and bulkheads in the double bottom hull buckled. 1,410 tons of water flooded the ship, there was a lot of internal damage to pipes etc and Turret Dora was thrown from its bearings and could not be rotated. The ship's two floatplanes were completely destroyed. Repairs lasted until 2 April 1944.

Operation Tungsten, saw 40 Barracuda dive-bombers carrying 1,600lb armour-piercing bombs and 40 fighters attack in 2 waves; they scored 15 direct hits and 2 near misses. The aircraft achieved complete surprise; only 1 was lost in the 1st wave as it took 12-14 minutes for all of Tirpitz's AA batteries to be fully manned. The 2nd wave arrived an hour later but despite the alertness of the German gunners, only 1 bomber was lost.

The bombs did not penetrate the main armour but did cause significant damage to the ship's superstructure, and inflicted serious casualties: 122 men were killed and 316 wounded. Two 15cm turrets and both Arado 196 floatplanes were destroyed. Several hits caused serious fires; concussive shock disabled the starboard engine, and 2,000 tons of water flooded the ship.

Regardless of the cost, Dönitz ordered the ship be repaired, although Tirpitz could no longer be used in a surface action because of insufficient fighter support. Repairs began in early May and by 2 June, the ship was again able to steam. Also, during the repair process, the 15cm guns were modified to allow their use against aircraft, and specially-fuzed 38cm shells for barrage anti-aircraft fire were supplied.

A series of carrier strikes were planned over the next 3 months, but bad weather forced their cancellation. These were Operations Planet, Brawn, Tiger Claw and Mascot.

Operations Goodwood I and II were launched on 22 August; a carrier force launched 38 bombers and 43 fighters between the two raids. The attacks caused no damage to Tirpitz and 3 aircraft were lost. Goodwood III followed on 24th August: 48 bombers and 29 fighters attacked the ship but only scored 2 hits which caused minor damage. A 1,600lb bomb, penetrated the upper and lower armour decks and came to rest in her No. 4 switchboard room. As its fuze was damaged, the bomb did not detonate. The second, a 500lb bomb, exploded causing superficial damage: 6 planes were lost. Goodwood IV followed on the 29th, with 34 bombers and 25 fighters; heavy fog prevented any hits. Tirpitz shot down a Firefly and a Corsair. The ship fired 54 rounds from her main guns, 161 from the 15 cm guns and used up 20% of her light anti-aircraft ammunition.

The ineffectiveness of the Fleet Air Arm led to the task being given to the RAF's No. 5 Group who decided to use Lancaster bombers and 6-ton Tallboy bombs to penetrate the ship's heavy armour.

The first attack, Operation Paravane, took place on 15th September 1944, operating from a forward base at Yagodnik in Russia. 23 Lancasters (17 carrying Tallboys and 6 each carrying 12 Johnnie Walker mines) attacked. My dad's plane didn't make it to Russia as, on take off, the Tallboy swung on its release strap and its tail fins got stuck in the rear of the bomb-bay. Despite violent manoeuvring, P/O Lake could not shake it free over the sea so my father had to try to undo the massive restraining nut with, and I quote, “A bloody big spanner!” However, the threaded bolt was very long and with the 6 ton mass pulling down, it proved an impossible task. More pitching up and down followed until finally, it worked: the bomb fell away into the North Sea.

The actual attack scored a single hit on the ship's bow. This was by IX Squadron's Dougie Melrose flying WS-J (nickname Johnnie Walker, but ironically, not carrying Johnnie Walker mines). I was told that suddenly the target came into view through the smoke and moments later, the bomb aimer dropped the bomb. The Tallboy penetrated the ship, exited through the keel, and exploded in the bottom of the fjord. The bow was flooded with approx 850 tons of water and concussive shock caused severe damage to fire-control equipment. The damage persuaded the Germans to repair the ship for use only as a floating gun battery. On 15th October, the ship made the 230 mile trip to Tromsø under her own power; it would be her last.

617 and IX squadrons made a second attempt on 29th October, after the ship was moored off Håkøya Island outside Tromsø. 32 Lancasters attacked the ship with Tallboys during Operation Obviate, which resulted in only one near miss, due to the effective smoke screen and the bad weather over the target. The port rudder and shaft, were damaged and there was some flooding. Tirpitz's 38cm fragmentation shells proved ineffective against high-flying bombers but 1 aircraft was damaged by shore-based AA guns.

Subsequently, the ship's anchorage was significantly improved. A large sandbank was constructed under and around the ship to prevent her from capsizing, and anti-torpedo nets were installed. The ship was also prepared for her role as a floating artillery platform: the crew was reduced to 1,600.

12th November 1944: the final attack on Tirpitz. The planned route had been worked out weeks before using data from radar reconnaissance aircraft which had found a gap in the coastal coverage. Unfortunately, not all the Lancasters took off – 7 IX squadron aircraft were grounded due to icing. Not all aircraft navigated their way accurately and were picked up by the radar on Donna Island. Tirpitz was warned and sent Bardufoss airfield an alert at around 08:52. At 08:55 sirens began sounding in Tromsø, and the town's guns were manned, shells fused and barrels pointed south and skywards. On Tirpitz, water-tight doors were closed and all 110 of her guns, of every calibre, prepared to fire. Likewise, the shore-based and flak-ship batteries.

At 09:00, the aircraft reached Lake Tournetrask, 85 miles from the Tirpitz and began to climb from their radar avoiding 2,000ft to their bombing altitude of 16,000ft. This would take 65 miles, leaving a 20 mile, 7 minute run-in to the target.

The aircraft were spotted at 09:05 by the ship's lookouts, using binoculars, at 70 miles distance, but as they weren't heading towards the ship, were initially ignored. 8 of the Lancasters were off course and flew directly over Bardufoss airfield; those on the ground expected to be bombed but nothing happened. Pilots then began running to their planes but as it was a badly designed airfield, it took a long time to get ready and airborne, as the fighters had to go all the way down the runway, before turning completely round to take off.

At 09:40, at a slant range of 13 miles, Tirpitz used her 38cm guns against the bombers; the 4 forward main guns fired simultaneously. The noise echoed round the mountains and rolled down the fjord. A minute later the 15cm guns opened up at a range of 9 miles and then the quick-firing guns joined in. But the force of 30 Lancasters pressed on though the mounting hailstorm of flak and dropped 29 Tallboys on the ship – 1 Lancaster was there to film the raid.

Flying in a V formation the Tallboys were released by Wing Commander JB Tait and the 4 other aircraft in the first wave at 09:43. Dropped from 16,000ft, each reached a terminal velocity of about the speed of sound during their 30 second fall. 617 claim that bomb 1, dropped by Tait's bomb-aimer, Danials, hit amidships. The second hit near the bow, the third hit Hakoya island causing a landslide which silenced the AA batteries. The fourth hit the after range finder, the fifth hit the water on the port beam and her guns fell silent. But the film backs up the account of Sqn Ldr Bill Williams in WS-A: bomb 1 – near miss; 2 – fell short; 3 – hit Hakoya; 4 – direct hit and guns stopped.

Delayed action fuses enabled deep penetration to ensure maximum damage when the 5.5 ton, Torpex-filled warhead detonated, disembowelling the vessel. Windows in the town and surrounding buildings, even over a mile away, shattered.

5 seconds after the 1st bomb struck, the second one arrived – and so it would continue in rapid succession until all the bombs had fallen. A series of 3 fell in by the port beam and the 52,000 ton ship lurched so violently that the mooring chains, each link as thick as a man's wrist, snapped like thread. One Tallboy hit the deck but despite its unbelievable momentum and design, failed to penetrate the armour, ricocheted off and landed, broken and twisted, 200 yards away on the shore.

Two minutes after the 1st 617 bomb fell, IX Squadron had begun releasing theirs. Dougie Tweddle dropped the last bomb from WS-Y (William Younger) at 09:49. In total, the raid had taken just 6 minutes. As his Lancaster flew out of sight his rear gunner saw her roll over.

How? Several bombs which landed within the anti-torpedo net barrier had caused significant cratering and movement of the seabed, removing much of the sandbank that had been constructed to prevent the ship from capsizing. To make matters worse, the tide was at full flood and the suction caused by the subsurface explosions close to her port side had pulled her further away from the shallows.

A bomb which penetrated the ship's deck between turrets Anton and Bruno failed to explode. The hit amidships between the aircraft catapult and the funnel caused severe damage. A huge hole was blown in the ship's side and bottom; an entire section of belt armour (about 120 feet of 12 inch armour plate) abreast of the bomb hit was completely ripped away.

Now, to quote Wikipedia, “A third bomb may have struck the port side of turret Caesar ...” This hit, according to IX squadron's own record of the debrief, was scored by WS-V, my father's plane. It says, “5 bombs seen to fall. No1 – 50 yards off bow of ship. No 2 slightly undershot centre of ship. No 3 – about 30 yards from stern. No 4 – overshot centre of ship by about 150 yards. No 5 – overshot to the right by about 150 yards. In addition rear gunner saw own bomb which he considers hit the ship as a big explosion and fire followed immediately.”

From the translated Norwegian article; “...There was a direct hit on the forrard gun position, on the bridge and behind the funnel, while others struck close to the hull. Then a bomb hit the magazine and a huge column of smoke climbed into the air. For several more minutes the bombing continued, in a hell of a noise which echoed among the mountains. When the planes saw the task was done they flew home. The last one saw the battleship slowly settle over on her side.”

The hit amidships caused massive flooding and she listed to port. Captain Weber ordered, 'abandon ship' at 09:51 as the list increased to 60 degrees; minutes later, a large explosion rocked turret Caesar as a magazine blew up. The turret roof and part of the rotating structure were thrown 25m into the air and onto a group of men swimming to the shore, crushing them. Tirpitz then rolled over and buried her smashed superstructure into the sea floor – finished.

Major Heinrich Ehrler, the commander of III./Jagdgeschwader 5, was blamed for the Luftwaffe's failure to intercept or engage the British bombers. At his court-martial, the evidence said that his unit had failed to help the Kriegsmarine when requested. He was sentenced to 3 years in prison, but he was released after a month, demoted, and reassigned. Ehrler was later cleared by further investigations which concluded poor communication between the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe had caused the debacle; the airmen had not been informed that Tirpitz had been moved off Håkøya two weeks before the attack.

A recent TV documentary has also claimed that a German, an allied sympathiser, failed to send Tirpitz's crucial requests for help to the Luftwaffe base until it was too late.

Only 1 Lancaster failed to return that day. It was IX Squadron's WS-T, flown by P/O Coster who nursed his flak-damaged aircraft back to Sweden where it crash landed but everyone survived relatively unscathed. It could have been so different if Oberleutnant Werner Gayko, the commander of the 9th Squadron of Geschwader 5's Focke-Wulfs, hadn't had a nightmare mission.

His comrades had managed to get into the air in dribs and drabs and climbed for height, but the Lancasters which had overflown Bardufoss had long since disappeared. Not having received the warning and not knowing about the Tirpitz's location, they awaited instructions, whilst Gayko struggled to start his engine!

At 09:55 he arrived over Tromsø and saw, “a large ship lying keel up.” His men were returning to base and he turned to do the same. Then he spotted P/O Coster's crippled Lancaster and decided to exact revenge. He pursued it, dropped in behind and fired. His four 20mm cannons fired a few rounds then – nothing: he'd had a stoppage. Gayko pulled away to clear his guns and went in again, but more trouble with his cannons. Suddenly he realised he was flying over the Swedish frontier – something he'd done before and the terrible trouble it had caused him was never to be repeated under any circumstances. So he turned away.

For the RAF, not 1 airman was lost. The Beast had been sunk and congratulations and jubilations were heaped on those who'd done it.

Meanwhile, trapped inside a cold, pitch-black compartment in the smashed and mangled hull, 200 young sailors sang lustily until their oxygen ran out. 82 others were rescued through holes painstakingly cut through the upturned keel, giving the final lie to the short communique by Goebbels who said, “The battleship Tirpitz, used to protect the North Norwegian coast during the last 2 years, has repelled numerous air attacks by strong British formations of special purpose bombers and has shot down many aircraft.

“On the 12th November the Tirpitz was again attacked by British aircraft with super heavy bombs. She was put out of action immediately off the Norwegian coast in shallow water. Most of the crew were saved.”

In writing this paper, my thoughts are with all those who lost their lives 76 years ago, Terje Jacobsen of the resistance who treated mum and me so well, and Leif Arneberg who gave us the Tirpitz's crest and torpedo-net ring. (Ian Baird 2020)